The following post is actually a re-post (having originally appeared on August 27, 2007) from Hill Country of Monroe County, Mississippi: A Weblog by Terry Thornton. I’m thrilled to be able to post it here again, with Terry’s permission. It’s an absolutely wonderful piece of Civil War “memory” and it fits extremely well within the environment of this blog. Note that this piece is copyright protected and used only with permission. Thanks again Terry!

Monday, August 27, 2007

Shhhhhhhhhhhhh! Let’s not talk about this . . .

by Terry Thornton

I am a Mississippian by birth and I am a Mississippian by choice. Of the forty-seven years that have passed since I turned twenty-one years of age, I have spent the majority living in other states electing to return to inside the Magnolia Curtain to live out my retirement.

I am a Southerner.

Growing up in the Hill Country of eastern Monroe County during those peaceful decades prior to the turbulent 1960s, I learned some about our region’s history and heritage but little about my Thornton family history. My father was somewhat distant to his larger family both in temperament and in geography — that, combined with the Thornton tendency to withhold information mitigated against my learning much about my ancestors.

I got most of my information from overhearing snatches and snippets of conversations while listening from the chimney corner. And as I grew older I learned that perhaps not all of the solid Southern unity was as it was rumored and taught to be — that perhaps there were cracks in the solidarity in the Hill Country Confederate unity during that difficult time some seventy-eight years before I was born.

Some things didn’t add up.

But when I would ask, I was told, “Shhhhhhhhh. Let’s not talk about that.”

One of my favorite places to play during those safe years when children were permitted to play unsupervised away from home was at the New Hope Cemetery which was about one-half mile west of my home. Down the gravel road we would walk (no soccer moms with vans back then — nor any other vehicle; kids walked or rode bicycles) sometimes eight or ten or more to play all afternoon among the cool stone markers in the graveyard. Although the graveyard then was kept free of grass (as was the custom for most Hill Country houses: the yards were bare of grass), the cemetery had overgrown with trees creating large dense shaded places. And our favorite game to play in one of the large ornately decorated plots at the cemetery was “Civil War draft dodger.”

The older kids taught us how to play the game; they had been taught the game from the generation just older than them; and they in turn probably heard the stories from those who lived the experience upon which we had made a game. To play the game, one had to hide from the CSA draft enforcers. The place to hide was a special room underground at the cemetery in a specific family plot which had a false grave built for the purpose of hiding out. When the enforcers were in the area, you had to hide in the grave; when the enforcers were not close by, you had to hide in the dense woods and creek bottom just to the south of the cemetery.

When I was a child playing there, the family plot had been modified; the false grave had been used for an actual burial. So when we hid in the special “room” we just lay between the graves crowded into that family burial plot with its interesting stones and low fencing all around.

If the enforcers came and stayed a few days, the ones hidden in the grave were nourished by “grieving” mothers, sisters, or girlfriends who would come to the graveyard with baskets of flowers which contained food and water. And as the grieving females knelt there “praying” they were really whispering the latest news to those hidden just below.

I could never decide which role I enjoyed playing best: enforcer on horseback charging up and dragging folks off to fight or dodger lying there in the cemetery while all the pretty girls brought me food, water, and flowers and whispered directions to me as I rested in the perfect pacifist position.

To play “draft dodger” when I was a child involved a large cast of characters. There were roles for everyone no matter who all came to play that day — and we played the game often. But as I grew older, I listened to my teachers who were of the opinion that all true Southerners were loyal and 100% committed to fighting the Yankees!

If that were the case, I thought, then why were there hidden rooms in the graveyard at Parham? Maybe I had it mixed up; maybe those hidden men were really good brave loyal Southerners hiding from the Yankees.

Again came the, “Shhhhhhhhh. Let’s not talk about this” from the adults in my life.

But the older kids checked the story out with the older ones who would tell us the straight of it — the ones hiding were hiding from the Southern draft enforcers.

Then I overheard a conversation between my father and one of his relatives.

What? Some of the Thorntons were in the Union Army? Whoa! I thought. How did that happen? And no one would talk to me about the event or even acknowledge what I had overheard.

“Shhhhhhhh. Let’s not talk about this.”

As I got older I also questioned why the given name Sherman was widely used in my family: my grandfather had Sherman as one of his given names; my father had Sherman as one of his given names; my brothers has Sherman as one of his given names; and I have at least two cousins with Sherman as one of their given names. Somehow this choice of given name didn’t square with my conception of the turmoil that ripped through the Hills of Alabama and Mississippi some seventy-five years before I was born.

General Sherman was not one of my favorite people — he was not presented in any favorable light in any of the lessons in history I had at Hatley School. So what was I doing in a family with so many males named for Sherman? Oh well, I was told, they are named for someone else but that someone was never identified.

And if I persisted, out came the, “Shhhhhhhhhh. Let’s not talk about this.”

About 1970, my father asked my wife and me to go with him to Lann Cemetery, Splunge, Monroe County, Mississippi, to visit the grave of James Monroe Thornton. James Monroe Thornton was my father’s grandfather — James Monroe Thornton was the one who first named a son with the moniker “Sherman” — in 1865 he named a son John Sherman Thornton.

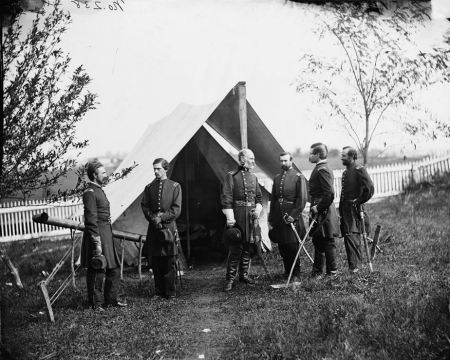

And while at the cemetery, my father told my wife what he had never told me: James Monroe Thornton served in the Union Army. Basically all he would or could tell me was that his grandfather, he had been told, was on the staff with General Sherman, had attained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and so admired the General that he vowed to name the first of his sons born after the war for the general.

James Monroe Thornton survived the war and when the first child born after the war was a son, he named him John Sherman Thornton.

Be damned if I would listen to another “Shhhhhhhh. Let’s not talk about this” again!

During the next year or two, I started my reading and researching of the Thornton family. I learned that during the awful war years, both before and after, that they lived in the general area of Walker and Fayette Counties, Alabama. The Thornton family did not arrive in Mississippi until between 1905 to 1910. I discovered the gem of a book, Tories of the Hills, by Wesley S. Thompson (Winfield, Alabama: The Pareil Press. 1960). [My edition is the Civil War Centennial Edition, a limited-re-printing from Northwest Alabama Publishing Company, Jasper, Alabama.]

Thompson states in his Introduction “those opposed to the Secession . . . were called . . . Tories from the hills. . . met in a Convention July 4, 1861, and drew up resolutions to secede from the State [of Alabama]. When this . . . failed [the Tories] took to the coves and mountains for hiding rather than go to the Confederate Armies . . . there followed one of the bloodiest struggles of guerrilla-warfare ever fought on American soil.”

Suddenly the region known as “Freedom Hills,” a rugged area that spreads across the hill country of Alabama and west into Mississippi took on a new meaning.

Freedom! . . . no “Shhhhhhhhhh, let’s not talk about this” was going to stop me now.

So obviously the opposition to serving in the Confederate cause was as far west as the Hill Country in Monroe County, Mississippi, if hide-outs and resisting the draft were so commonplace that children’s games were organized and played almost 100 years after those sad events unfolded.

But learning more information from my father or from his larger family of their time in Alabama and of the Union Army connection to General Sherman was not to be. My father died a few years after telling me about his grandfather; the other older family members either didn’t know the family history or were not willing to talk about it. Some were of the opinion that we should not talk about the possibility of such an involvement!

And there I was, blocked in with “Shhhhhhh, let’s not talk about this” from cousins far and wide. But upon probing deeper, it was obvious that my cousins knew less than I about this part of our family’s history. The “Shhhhh, let’s not talk about this” mentality had prevented some of the most basic of family information from filtering down.

Several years went by and I began an email correspondence with a cousin, Lori Thornton, who was an experienced genealogist and computer expert. Lori and I compared notes and within a few months, I had the first documented evidence that my great-grandfather [and Lori’s great-great-grandfather] James Monroe Thornton had indeed served in the First Alabama Cavalry USA.

And upon learning about this documented fact, I had relatives to send me word, “Shhhhhh. Let’s not talk about this.”

The first evidence I had of James Monroe Thornton’s military service in the First Alabama Cavalry U.S.A. was from Glenda McWhirter Todd’s in-depth study, First Alabama Cavalry USA: Homage to Patriotism (Bowie, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc. 1999). There on page 368 is this entry, the first evidence I had of my great-grandfather’s involvement:

Thornton, James M., Pvt., Co. A, age 38, EN 3/23/63 & MI 3/24/63, Glendale, MS, on daily duty as teamster, MO 12/22/63, Memphis, TN.

James Monroe Thornton enlisted in the First Alabama Cavalry USA at Glendale, Mississippi on March 23, 1863. The next day he was mustered into service. He was assigned to Company A; he was given the rank of Private. He was 38 years old. He served daily duty as a teamster and was mustered out of service just before Christmas, December 22, 1863, in Memphis, Tennessee.

My father had been misinformed about James Monroe Thornton’s rank — there had been some huge and grand promotions for Private Thornton to have attained the lofty status of Lieutenant Colonel — whether that embellishment in rank was done by James Monroe Thornton himself (he lived to the ripe old age of 88 years) or by others is unknown.

Lori and I ordered the service record and the pension file for our common ancestor — and there learned for the first time the extent of his military service. James Monroe Thornton indeed was in the First Alabama Cavalry USA; he was a Private. He was at home in Alabama hiding out from the Confederate enforcers most of the time he spent in the service of the Union. He accompanied a small group in June who was returned to Walker and Fayette County and while there became ill. His family hid him in the woods from July through early December when he returned to camp.

James Monroe Thornton was absent with leave from June 29, 1863 through about December 13, 1863 when he returned to duty just in time to be mustered out on December 22, 1863.

He was not, however, a Lieutenant Colonel nor was he an aide-de-camp to General Sherman! He drove a team of mules or horses and hauled materials with a wagon as a Private doing teamster duty.

In all of this research, however, the harsh reality of what happened to my Thornton family in the Hills of Alabama has been slowly uncovered. Lori and I are continuing to examine records that are telling us the painful story of our family — a story that heretofore had been so suppressed within the family that our generation had no clue to its reality. Here is a brief summary of some of the major discoveries.

Two of James Monroe Thornton’s brothers also served in the First Alabama Calvary USA. Those two brothers died in service. No one in my family of my generation had any knowledge of these men. As far as I know, their names were not known as family. The grave of one has been located at the Nashville National Cemetery where I conducted a memorial on the occasion of the 140th anniversary of his death. It is believed that the first time that any of this young man’s family visited his grave site was 140 years after his death.

The “Shhhhhhh. Let’s not talk about this” time was over.

A third brother may have been killed by Confederate enforcers as he was making his way to the Union lines to volunteer. Lori and I are still working on this possibility. We know that a third brother disappears from all records during the Civil War years and we are intrigued by a statement recently discovered in his mother’s federal pension file about this possibility. More work is needed.

And perhaps the saddest chapter in all of this that was never talked about in my family is evidence that three of James Monroe Thornton’s brothers also served in the Confederate Army. One was captured in battle in Kentucky and eventually exchanged/released in Mississippi. We think he returned straight to North Alabama, visited briefly with his wife and child and other family nearby, and then with his older brother, James Monroe Thornton, walked over to Glendale, Mississippi and enrolled together. James Monroe survived; the brother he enlisted with died.

The youngest brother in that large family also died in the service of the Union Army. He and another brother had enrolled in the Confederate Army and both are listed as deserting at Tuscaloosa. The younger brother shows up on the First Alabama Cavalry USA enlistment rosters a month later; the other brother disappears from the records. It is presumed that he is the one his mother later states was killed by enforcers while making his way to the Union line.

So I can’t tell you about a great-grandfather who was a Lieutenant Colonel in General Sherman’s army — but I can talk a bit about his service as a Private, as a teamster, during a few short months during the Civil War. I can tell you a bit about the history of the South and can confirm that the solidarity and Confederate unity wasn’t what we’ve been taught in the public schools of Mississippi.

But, listen, someone is saying, “Shhhhhhhhh. Let’s not talk about this!”

[Editor’s (Terry’s) Note: This recollection was submitted to the current Carnival of Genealogy. The 31st Carnival has as its topic Confirm or Debunk: Family Myths, Legends, and Lore, and is being hosted by Craig Manson at GeneaBlogie.]